Making Rejection Your Ally

For musician of any sort, rejection is a common occurrence…and I’ll be honest, that sucks. Whether it's a rejection letter from a publisher or record label, a negative review from a critic, or not getting the gig you wanted, rejection can be a tough pill to swallow. But rejection doesn't have to be 100% bad. In fact, if you approach it with the right mindset, rejection can be a powerful ally to help you grow as a musician. So, today I want to give some tips I’ve learned on how to deal with rejection and use it to your advantage.

1. Don’t take it personally

First off, remember that it's not personal. I know that’s easier said than done. When you're rejected, it doesn't mean that you're a bad musician or that your music isn't good enough. It simply means that the person or organization that rejected you didn't see a fit for you at this particular time. I understand that doesn’t make it any easier. But. Remember that the music industry is subjective, and what one person likes, another person may not. So don't take rejection as a reflection of your talent or worth as a musician.

This is a rather difficult thing to do. What is more vulnerable than putting your art out into the world? More often than not, It’s not just something you made, but rather it’s a piece of you.

Let’s look at some of the more frequent causes of rejection:

Composition Competitions

Wow, do I have a lot of thoughts on composition competitions. Most of them are not relevant to this discussion so I’ll try to sort through what is pertinent. Each organization who puts together a competition like this probably has a particular sound in mind for the piece they’d like. If not, then you’re looking at dealing with the particular preference of the judges. Neither of these are a reflection on you as a composer.

I love watching cooking competitions. During the judging you’ll hear discrepancies like one judge saying “my meat is overcooked” or “it’s got too much salt for my liking”, and then the next judge will completely disagree with them and say that the dish was executed perfectly. In those moments, it’s hard not to think about composition competitions and the judging that goes on behind the scenes that the composers don’t know about. I have no idea what those judges are looking for - music is a subjective art, not an objective sport. Maybe that judge just wanted a little more chromaticism, a little less polyphony, or any number of other things.

Many of these competitions even require you to take your name off before you submit, so it’s really not personal in those cases. It still feels that way sometimes.

Labels and Publishers

I feel like it’s probably difficult to overstate how many submissions labels and publishers get from musicians on a daily basis.

I once sent in a choir piece to a music publisher that I was rather proud of. The choir who commissioned it had done a spectacular job with the premiere. I was encouraged by the director of that choir to send it to a particular publisher that they had a connection to. After months of waiting, I finally got a response: “This is a beautiful piece! I love it! Unfortunately, we are going to have to pass because we don’t think it will sell all that well.”

Sometimes it’s very obvious that you aren’t the correct fit with a label or a publisher. I’m probably not getting too many record deals by sending my demo off to a heavy metal label - and that doesn’t cause me any pain. It’s when it seems like you would be a good fit, and the executives disagree that this gets hard.

University Music Programs

I’m not even going to pretend that I have even a 1% understanding of the university admissions process. But it’s definitely a common source of rejection among musicians.

Concluding this section: Some composers specifically try to get rejected a certain number of times per year. This does a few things: 1) it’s proof you’re putting yourself out there, 2) gives you a better chance of being accepted for something, and 3) firmly accepts rejection as an unavoidable reality, and in so doing that takes away some of its sting.

2. Look for constructive criticism

Okay, it’s one thing to not take it personally, and just shrug it off, but how can we use that rejection to move forward? One of the worst parts of most rejections letters is that there is absolutely no comment about why you were rejected. It feels like you sent your music to a magic 8 ball and it just responded “you lose, try again.” But. There are those times where we do receive comments that go along with the rejection; and that’s when we really need to take an honest look at what suggestions have been offered. I will be honest and say that I spent a lot of the first decade of my career dismissing suggestions I was given because they just ‘didn’t understand’ the piece. Yeah, that was dumb.

Look for any constructive criticism that can help you improve. This may come in the form of feedback from a record label or producer, or it may be in the form of a negative review that points out specific areas that need improvement - or even from a performer who played your piece. While it can be tough to hear criticism about your music, try to take it as an opportunity to learn and grow. Look for the nuggets of truth in the criticism and use them to make your music better.

What to keep, and what not to

This is a really tough question to answer. I would say there are kind of three categories of responses to criticism?

What you immediately should dismiss.

Is it constructive? If not, get rid of it. If you implemented that suggestion, would it go against who you are as a composer? If so, dismiss it. Like I said earlier, deciding what to dismiss can be a hard rope to balance on (mostly from youthful arrogance), but over time I think it becomes easier to recognize what you should immediately dismiss.What you should implement right away.

If your comments said something like “violins can’t play this passage,” or, “This notation is unreadable”, or “You forgot to transpose your horn part” (all comments I’ve gotten) - fix those things immediately. These have less to do with your musicality, and are more technical in nature. Always take those as a learning opportunity, and try your hardest to not make those mistakes twice.What you should file away for later.

I think the majority of feedback we get on our music falls in this category. Maybe we didn’t fully understand the suggestion at the time, but after some thought, it was correct. Or, maybe it was a suggestion that you a little uncomfortable hearing, but then thought “what if I did experiment with trying that?” I think a lot more of the comments we receive are applicable to us than we may think at first.

3. What can you do better?

The unpleasant truth is that rejection can be a valuable learning experience. Take some time to reflect on what went wrong and how you can improve for next time. Did you not prepare enough for the audition or interview? Did you not have the right materials or press kit? Did you not research the organization or individual enough before approaching them? If you know of the specific reason for the rejection, use it as a learning opportunity to make sure you're better prepared next time. Of course, sometimes you do everything right and it still doesn’t work out…so for that, refer back to section 1.

An opportunity for Improvement

As artists, our relentless pursuit should be in getting better at our art. Rejection and criticism offers us that very chance. And it gives us a perspective that is very different than our own. Blind spots are notoriously hard to see.

What if your favorite part of the song is the very thing that is making the song not work? You’ve got to be willing to part with it. Cut your best material if it isn’t right for the piece (but don’t throw it away, find some other, better suited spot for it).

Teachability

A lot of it comes down to how teachable you are willing to be. It’s like a parent who insists their child can’t be the problem because their child is perfect. You’re going to miss a lot of opportunities for improvement based on how willing you are to change what needs to be changed, and to learn what needs to be learned.

Practice.

Every musician hears this every single minute of our lives, so I won’t linger here too long. But, yeah. Practice your craft. And I’ll turn the mirror back at me and tell me to practice my craft too.

4. Stay positive

It's easy to get discouraged after being rejected, but it's important to stay positive. Remember that rejection is a part of the music industry, and every successful musician has faced rejection at some point. Use rejection as motivation to work harder and improve your music. Focus on the positive feedback you've received and the progress you've made so far. Remember why you started making music in the first place, and let that passion drive you forward.

The value of your music

Here’s the truth: your music has intrinsic value by the very fact that you saw enough value in it to make it in the first place. And there is an audience for it. I also know how difficult it is - even with how connected we are through the internet - to find that audience. Someone is out there, who upon finding your music will say “wow, I wish I had known about this sooner.”

5. Keep moving forward

Finally, don't let rejection stop you from pursuing your dreams. Keep moving forward and continue to make music. Remember that success in the music industry often comes after many rejections and setbacks. Keep honing your craft and seeking out new opportunities. The more you put yourself out there, the more chances you have of finding success.

Start on the next one.

There’s a great scene in “Tick, Tick Boom” where Jonathan Larson (played by Andrew Garfield) has just had a successful musical workshop, but didn’t receive any offers for his musical to be produced. He asks his agent “what should I do now?” or something to that effect, and she simply responds: “Get to work on the next one.”

Conclusion

Remember first and foremost that rejection is subjective. What one person may reject, another person may embrace. Keep that in mind as you continue to pursue your music career. Don't let rejection define you or your music. Keep creating, keep learning, and keep pushing forward. Eventually, I believe your hard work and perseverance will pay off.

Use rejection as an opportunity to learn and grow, and don't take it personally. Look for constructive criticism, learn from the experience, stay positive, and keep moving forward. With these tips, you can turn rejection into an ally to help you achieve your musical goals.

Starting a New Piece

I thought maybe I would share 3 strategies that helped me overcome writer’s block, and actually start this project.

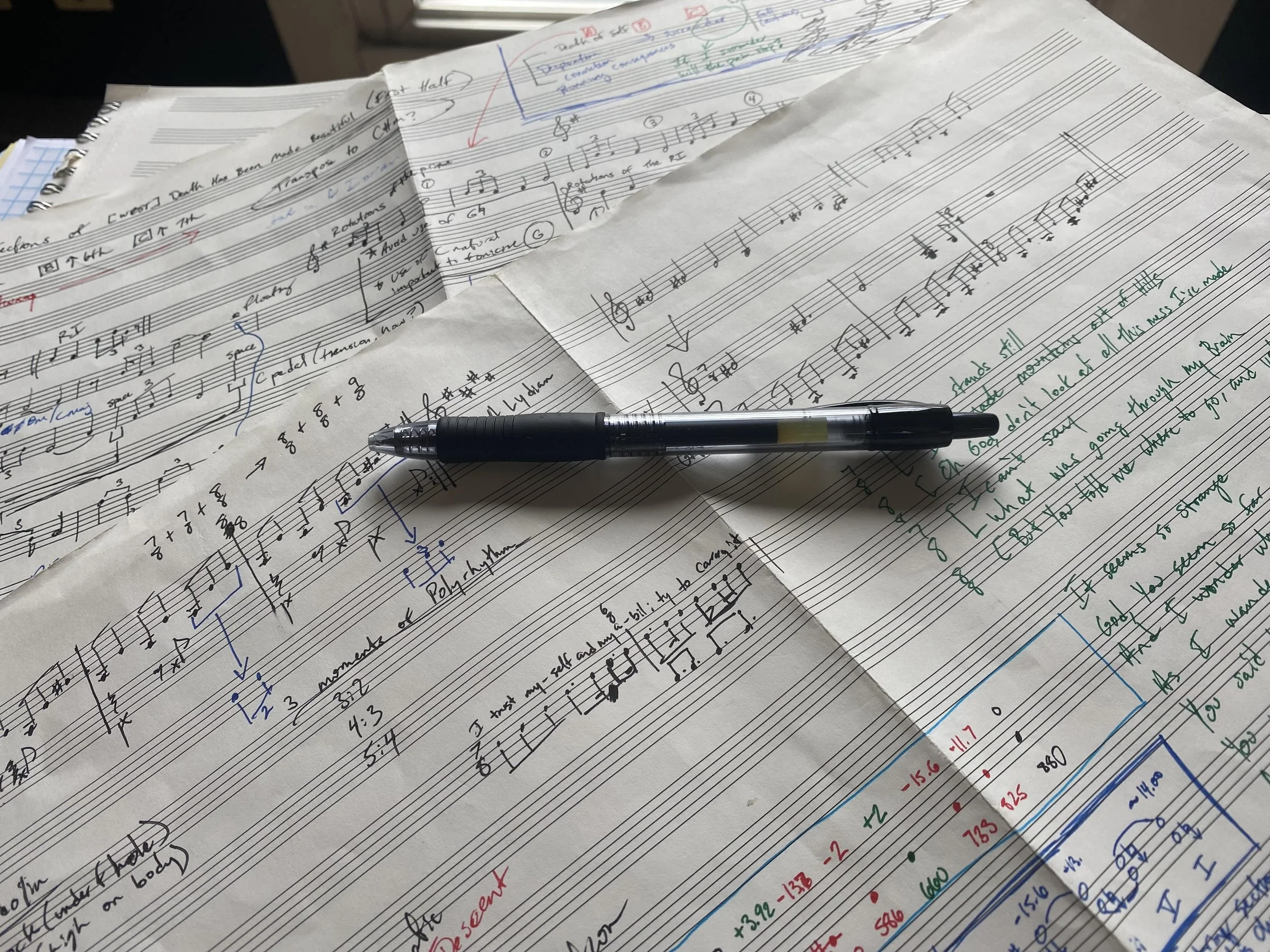

I’m starting a brand new piece today. I’ve had this idea for a while, but it’s just been sitting in my notebook.

So, I thought maybe I would share 3 strategies that helped me overcome writer’s block, and actually start this project. I’ll be coming at this from a composer’s perspective, but I imagine these strategies probably would transfer to just about any creative endeavor.

1. Start with what you have

What’s in your sketchbook

That stuff you doodle on a napkin

Voice memos you made on your phone

Is there anything you’ve already thought of that can be the basis for your new project?

Are there multiple fragments in your sketchbook that could be combined for this project?

For this piece, I’m starting with a melodic fragment that I found in my notebook (and the concept of “home”, but more on starting with concepts in a little bit). Those little fragments can be expanded to create an entire piece. It does need to be the right fit though, so it’s helpful to have a notebook full of possibilities.

So, If you haven’t already, start a sketchbook/ideas notebook/Voice Memo Catalog. This can be great for starting projects, but it can be especially helpful for all of those times you’re working on something else, but you’ve got a really good but totally unrelated idea.

2. Start with a Story, an Emotion, or a Picture

Sometimes the story comes to me before any music does.

Pick an emotion, any emotion will do. Then brainstorm every single way to evoke that emotion in musical terms. I also like to ask what is the opposite of that emotion, which can give the piece a nice contrast.

Start with a picture in your head: How would you create that scene in music? How would this look in another artform? For example, how would my music look if it was a painting? What would this piece be as a film?

I’ve been pondering different ideas of “home” for a while, and I think that will be the basis for this piece. Perhaps each idea of home can be the basis for each movement, we’ll see. But, having that concept in mind allows me to then think about how to translate that to music.

3. Set a limitation

With literally every possibility sitting before you, it can be extremely intimidating to actually start down a path. All art requires a limitation, or it would never get made. If I just choose the instruments I’ll use, and the length of the piece, I’ve excluded a lot right there, right off the bat. This is really helpful, because you now no longer have to worry about the millions of possibilities you won’t pursue in this project.

I’m starting with cello, and piano, and I want it to be about 10 minutes long.

Take away something. What if you tried to write with no melody? I find this very helpful especially if you tend to do something all the time. I tend to focus too much on melody, so taking it away can really help you focus on other things and come up with something different. You can discover a lot of cool ideas when you are forced to do something different than usual. If you always write in G major with 4/4 time, force yourself to write in anything other than G major 4/4.

Start with a limiting concept. Like a piece built entirely on 3rds. Or, a unique scale to work with. Or, never use C#.

Hopefully, that gave you some piece motivation or inspiration for starting your next project. I should probably stop procrastinating and get back to writing.

Should You Update Your Old Music?

I’m entering year 12 of my composition career. And here’s the thing: a lot of the music I wrote in those first few years is not quite up to my current standards. I’ve improved a lot - which is definitely what you want. A lot of that early music got one or maybe two performances and they’ve kinda just been collecting dust ever since. Or, maybe it’s a song on an early album that receives exactly 2 streams per year.

I was recently asked if I have any works for a particular choir voicing - and I did…but it’s one of those old pieces. I’m not exactly sure I want to hand that piece to an ensemble. We probably all have those moments where we look back on our past work and think: “what was I thinking? Violins don’t even have that note”, “these lyrics sound like they were written by a 3rd grader, and what’s with this guitar part?”, “I don’t even remember writing that”, or, “I’m confident the sopranos hate me for that - and they have every right to”.

That sent me down a rather deep rabbit hole: should I update my old music? Both from a practical and philosophical perspective. Should composers, in general, go back and fix the mistakes of their earlier works? If so, what exactly should they fix? Minor errors? Complete overhauls? All the above?

Today I want to look at the pros and cons of updating your old works, and I’ll let you know what I concluded about updating my own old works.

First let’s look at a few benefits of revisiting and revising your old music:

1. Make an unplayable piece performable.

Pieces that I wrote back in the day on the free version of Finale lacked any sort of regard for whether real life musicians could play that part. If a piece actually made it into the performer’s hands, they would usually tell me if a passage was awkward - or impossible. But that doesn’t mean that we always end up with a smooth, idiomatic part for all of our players, there’s a difference between “playable” and “comfortable”. Once I had a horn passage that was technically in the correct range, but it was the highest part of the range, and it stayed there for quite some time, and I forgot to include any places for the player to breathe. I think the guy’s lips fell off during one rehearsal.

If you’ve got a piece that you like but it has some problems like this, revising it could give the piece new life, or at least a longer life. This is especially important for composers that are self-published as you are your own editor 99% of the time - all mistakes in the score are your fault. And honestly, errors are like whack-a-mole - you take care of one of them and five more pop up in its place.

2. You didn’t have the resources at the time

Maybe you didn’t have the best quality microphone when you recorded it the first time. Maybe your voice has improved. Maybe you’ve gotten better at guitar and so you could record that solo the way you heard it in your head. Maybe you wanted a string quartet, but all you could find was a violin, a clarinet, and a tuba - so you went with that.

Revisiting an old piece can improve the quality of the piece if there are more resources available to you now. If you’ve been dissatisfied with the way a recording or a piece turned out the first time, and you feel like your artistic vision wasn’t fulfilled, this might be a good option.

3. Your artistic vision changed.

Now, this one is perhaps controversial from a philosophical point of view. But if you’re okay with doing a complete overhaul of your work, you might revisit a song because your vision has changed. Maybe you really like the original idea you had, but the execution of it back then is nothing like how you’d do it now. As you grow and evolve as an artist, your creative vision will change, and you can bring your old music in line with your current direction.

On a similar note, I’ve often been curious what it might sound like if some of my favorite artists took their earliest hits and did a “if I wrote this now” version. What if Toto wrote “Africa” today? What would that sound like? Some music (stylistically) is really the product of the time it was written and might not translate well to current styles, but it might be something worth trying with your old stuff.

Drawbacks to updating your old music:

1. It takes time away from new music

With all of these benefits listed above, you do have to consider the price: revising your old music takes time. And if you’re like me, you already find that 24 hours simply is not a long enough day. You’ve got to analyze whether the benefit of revising an old piece outweighs the cost of not working on a new piece.

2. For some, Philosophically, this is like “rewriting history”

For a number of composers, they feel like their entire life’s work should effectively serve as their musical auto-biography. In that sense, it would be like “rewriting” your personal history if you change past works, especially if it was just to bring it in line with your current vision.

And yeah, I kinda see that - if there is a lyric, or a musical moment that came out of a very specific moment in your life - it would change the meaning if you revised the piece.

3. Your fans might not like it.

Certain old music has a particular charm. Many people miss the noise that comes from old vinyls on the new digital music. If you’ve got a piece or a song that is well-loved, it might not be received well if you change it. Not that everything you do has to be to make the fans happy, it’s just something to consider.

Furthermore, you may not like it. You might spend all of this time revising, only to find out you like what you did in the first place better. Sometimes it is hard to capture that magic a second time. But also, it might not be fixable. There’s a profound frustration that festers from trying to resuscitate a piece that is already six feet underground.

So, how much should you revise?

This takes into consideration all of the pros and cons we just talked about. If you go with a “fix the errors” approach, that won’t take nearly as much time as a complete overhaul. I’d also argue that fixing minor errors doesn’t change your past artistic vision.

And if you do decide to revise a piece now, is there a point in the future that you’d want to update it again? Maybe that would be a waste of time…or, maybe it would be a cool series throughout your life to just update the same piece every 10 years or something like that.

Ultimately, it’s up to you. You know your own artistic vision and goals. So, what am I going to do? I’m going to fix enough errors so that all of my previous works are playable, and enjoyable. But, I’ll leave major structural changes in the past. Did I write a low F for a violin? I’ll fix it. Did I incorrectly place syllabic stress in a few places? Those are getting left alone.

I like the work that I’ve done, and I’d like for those pieces to continue. But I also stand by what I wrote back then, even if it isn’t up to my current standards, or what I would have done if I wrote it today.

So, what do you think about revisiting and revising your old music? Let me know in the comments!

How Ligeti Orchestrates A Motif

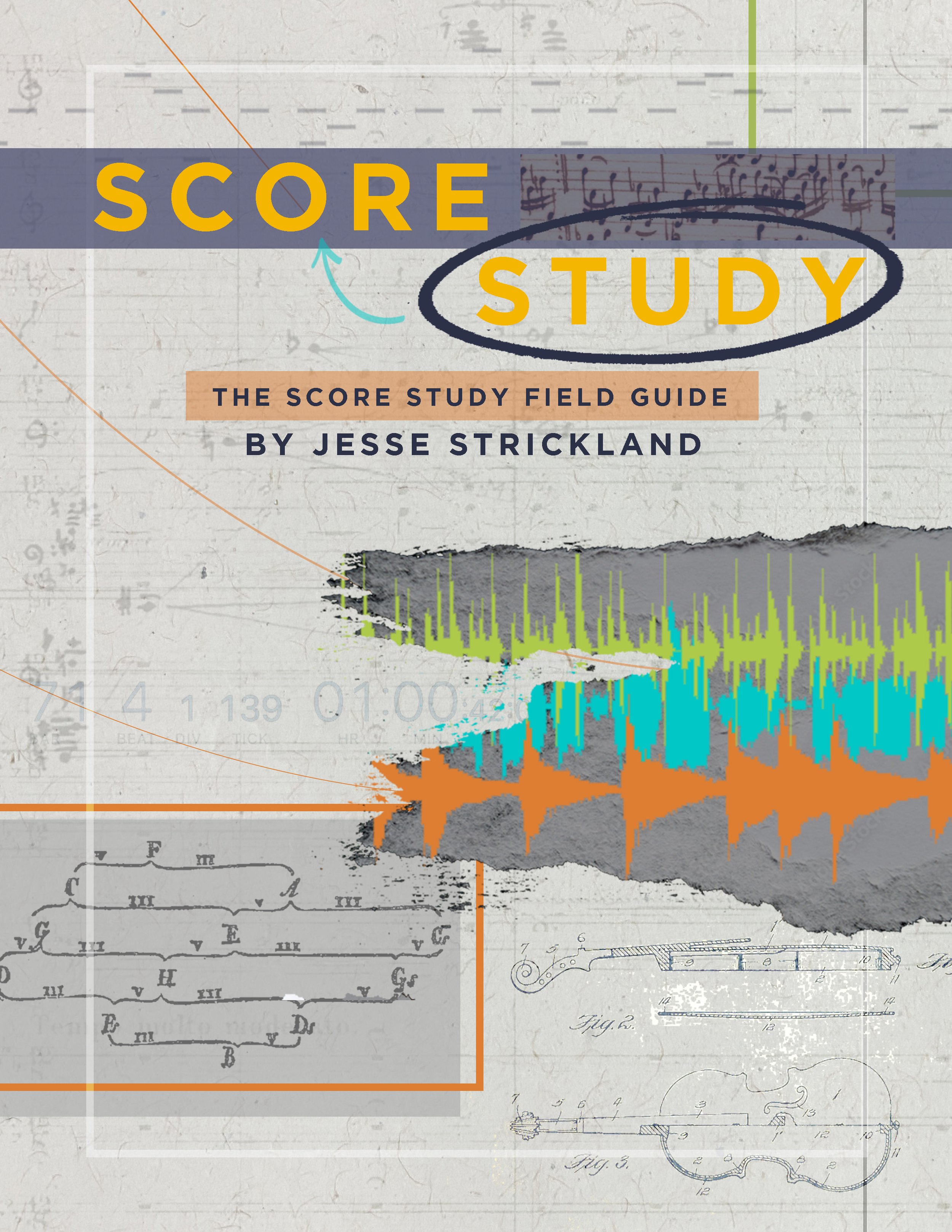

Orchestration can seem daunting. There can be too many possibilities, and there are a lot of instruments to keep up with. Today we're studying Ligeti's Ricercata III - looking at how he took a piece for solo piano, and orchestrated it for woodwind quintet (flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon).

Orchestration can seem daunting. There can be too many possibilities, and there are a lot of instruments to keep up with. Today we're studying Ligeti's Ricercata III - looking at how he took a piece for solo piano, and orchestrated it for woodwind quintet (flute, oboe, clarinet, horn, and bassoon).

Then in the second video, I'm taking my first ever piece for solo piano, and orchestrating it for woodwind quintet. I’ll be walking you through basic principles of orchestration based on the three ideas we talked about in the Ligeti orchestration.

Make sure to get your copy of the Score Study Field Guide in the resources section below.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Re-Writing My First Melody Using Music Theory

I get a lot of questions about how to use music theory to write music. So, today I'm taking a look at a melody I wrote a long time ago to see how I can improve it using concept we learn in Theory I and II.

I get a lot of questions about how to use music theory to write music. So, today I'm taking a look at a melody I wrote a long time ago to see how I can improve it using concept we learn in Theory I and II.

music theory resources

Looking for more music theory content?

Exclusive and curated content in composition, music theory, and musicology sent weekly to your inbox.

Featured Music Theory Course

Postcards

I’ve started a new instrumental composition series. Each piece in the series is written based on a photo that I took somewhere on this planet.

I’ve started a new instrumental composition series. Each piece in the series is written based on a photo that I took somewhere on this planet. In addition to the photos being a good creative prompt, each of them are meaningful memories to me. I’m planning for the first collection to have 10 Postcards.

I’ve got the first two here for you.

The first I took on the Little Platte River in Nebraska at our campground. As far as the music goes, the story is Sunset on the Little Platte River in Nebraska. Sleep is calling, but an active mind initially resists, but eventually succumbs.

The second is from the Upper West Side in New York City. It's called the city that never sleeps, so perhaps aptly, I took this photo at 2am the night from the roof of my building. Fun Fact, the photo was taken in late January, and you can still clearly see a Christmas Tree in one of the window on the right.

Afton Water Premiere

I'm excited to share with all of you a brand new world premiere! This is a choir piece I wrote back in 2019 for a commission that fell through. I liked the project enough that I went ahead and finished it. Fast forward to now, it received its world premiere back in December by the Armstrong Youth Chorus in Oklahoma under the direction of Mark Jenkins. Hope you enjoy!

Click here for the sheet music!

Magnify Your Name Music Video

As you may know by now, Evensong is HERE! You can get my new full-length studio album on Spotify, Apple, Amazon, and Pandora.

To go along with the release of Evensong, I’ve got a brand new music video that I’m excited to share with everyone! Magnify Your Name is the opening song on the album and serves as an overture for all of the musical styles that are to follow.

EVENSONG IS HERE

After nearly two years of work, I’m excited to announce that my new album Evensong is here!

Trappist-1: Percussion Quartet No. 1

The official video of my first Percussion Quartet!

The official video for my first Percussion Quartet is live on Facebook! Thanks to my friend Chase Banks and his wonderful team of percussionists for an excellent performance!

The piece itself is called Trappist-1, which refers to a Star System 29 light years from earth. It has 7 planets that all orbit their star closer than Mercury does to the sun. In order for this system to not collapse, the planets orbit each other in a very mathematical way, most of them orbiting their neighbor planet at a ratio of 3:2. In music, the 3:2 ratio is a Perfect 5th, and if you assign the outermost planet as C, then follow the ratios, you end up with a Cmaj9 chord - which is the basis of the piece. In addition, each planet was given a leitmotif, with each motif being proportional to the orbital period of the planet, using musical characteristics that match what we know about each planet. So, go check it out!

Interested in performing this piece? Score and Parts available here.

World Premiere - Clarinet Sonata No. 1

Brand new chamber work for clarinet and piano.

Last week, Steven Christ (Clarinet) and Annie Tindall-Gibson (Piano) premiered my first clarinet sonata at the University of South Carolina. The piece was commissioned by Steven Christ, and we’ve been collaborating on this project since late 2016 - so it was exciting to see it finally all come together.

Songs on the Mortality of Ice

New piece for chamber ensemble.

My new piece for chamber ensemble premiered last night as a part of the University of South Carolina's New Voices Concert. The piece was written for the Spark Ensemble.

Ireland Premiere

On tour with the South Carolina Concert Choir in Ireland!

I’m with the South Carolina Concert Choir over in Ireland for two weeks. The most exciting part about that, is that Hymn of Habakkuk - a choir piece I wrote back in 2014 - is getting its European premiere! It is being performed in three different cathedrals in three different cities. Which is very exciting. Below is the video of the performance in Galway. Thanks to the Concert Choir for their hard work on this piece. Y’all sound great. And yes…that is me on the right side of the screen.